The HL Hunley: First Submarine to Sink an Enemy Ship

The H.L. Hunley sunk the USS Housatonic in 1864.

The H.L. Hunley was a submarine built by the Confederate States of America in 1863, during the American Civil War. Two tragic mishaps during testing resulted in the deaths of 13 crewmen in Charleston Harbor, including its namesake, Horace Lawson Hunley. The Hunley was finally put into action in 1864, when it successfully ventured into the Atlantic Ocean, and rammed the USS Housatonic with its spar torpedo, and sank her. The Hunley was the first submarine to ever sink an enemy ship. But the submarine disappeared with its 8 crewmen, and its location remained a mystery for over a hundred years. Today, the HL Hunley resides at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in North Charleston, South Carolina.

This episode explores the history of early semi-submersible and submersible vessels, and the gradual development of submarine technology, including the Confederate built David class vessels, the Pioneer, American Diver, and finally the HL Hunley.

This episode is also available on YouTube: https://youtu.be/tCpgWaw0P4U

Written, edited, and produced by Rich Napolitano.

Original theme music for Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs by Sean Sigfried .

Go AD-FREE by becoming a Patreon Officer's Club Member!

Join at https://www.patreon.com.shipwreckspod

Join the Into History Network for ad-free access to this and many other fantastic history podcasts!

https://www.intohistory.com/shipwreckspod

Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs Merchandise is available!

https://shop.shipwrecksandseadogs.com/

You can support the podcast with a donation of any amount at:

https://www.buymeacoffee.com/shipwreckspod

Follow Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs

- Subscribe on YouTube

- Follow on BlueSky

- Follow on Threads

- Follow on Instagram

- F ollow on Facebook

The Hunley in a preservation tank at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center

An artist's drawing of the Hunley being prepared for launch.

The USS Housatonic

Horace Lawson Hunley was the primary benefactor behind the creation of the H.L. Hunley submarine.

Engineer James McClintock designed and built the H.L. Hunley.

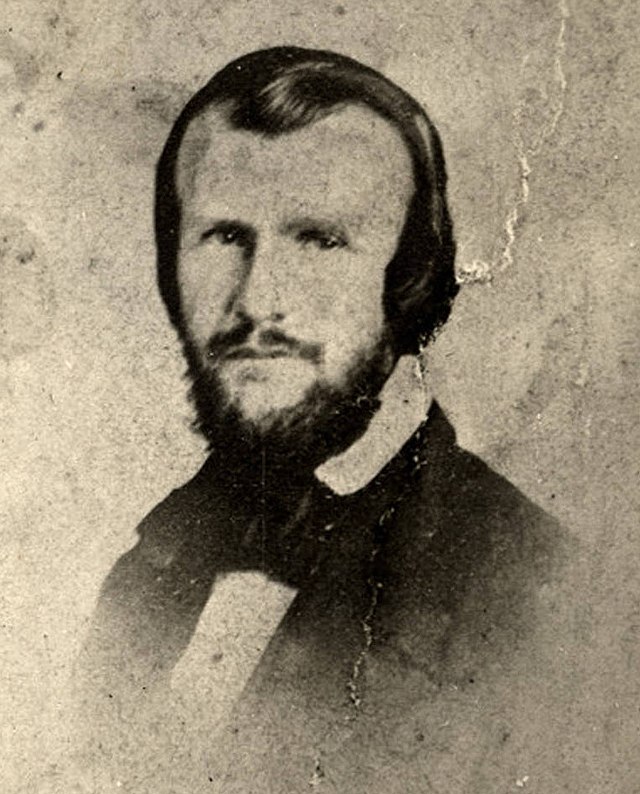

Lt. George Dixon

Researcher Maria Jacobsen hold the gold coin owned by George Dixon.

It is January 31, 1864. Lt. George Dixon of the Confederate States Army is in his quarters on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina. Dixon is the captain of the submarine, H.L Hunley, and he and his crew have been preparing for months to launch an attack of their secret weapon against the Union blockade of Charleston. Like many southern ports, the people of Charleston have been suffering under the stifling blockade for the last 3 years, and are desperate for relief. He is exhausted from the daily routine of walking from his quarters to the submarine docked at Breach Inlet, then venturing out into the Atlantic to train with his men. The hand-cranked propeller shaft was operated for hours, before the men returned to their base and walked again back to their quarters for much needed rest. Despite his exhaustion, Dixon sits down to write a letter by candlelight to his friend at home, Mr. Henry Willey.

Dear Friend Henry,

I suppose that you think it strange that I have not done anything here yet, but if I could tell you all of the circumstances that have occurred since I came here you would not think it strange of my not having done any execution as yet. But it would take considerable paper and time to relate them to you at present so I will postpone relating them until I see you. But there is one thing very evident, and that is to catch the Atlantic Ocean smooth during the winter months is considerable of an undertaking and one that I never wish to undertake again. Especially when all parties interested, sitting at home and wondering, and criticizing all of my actions, and saying why don't he do something. If I have not done anything, God Knows, it is not because I have not worked hard enough to do something. And I shall keep trying until I do something. I have been out-side several times but for various reasons I have not yet met with success. I am out-side every night in a small boat so it is not possible for any good night to pass without my being able to take advantage of it. I have my boat lying between Sullivan's and Long Islands and think that when the night does come, that I will surprise the Yankees completely. The Fleet offshore have drawings of the submarine and of course they have taken all precautions that it is possible for Yankee ingenuity to invent, but I hope to Flank them yet.

I have got very good quarters in sight of all of the Yankee and Confederate Batteries and can sit on the porch and see all of the guns that are fired. At present they are hammering away at Sumter but not doing so much damage so far. Their guns shake every window in the house so bad that you would imagine that they would break. The government has been very kind to me; they have given me everything that I have asked for. Give my regards to all engineering friends. Hoping to hear from you soon. I remain yours as ever,

Geo. E. Dixon

The H.L. Hunley: Death and Discovery

The recorded history of human beings venturing underwater dates back to antiquity. The Greek text “Problemata Physica”, mentions the Macedonian King Alexander the Great being lowered into a glass barrel, to observe the removal of obstacles in the harbor. Whether or not Alexander actually used a primitive diving bell such as this is unknown, but this is widely thought to be part of the Alexander Romance; a collection of myths that have grown and embellished over hundreds of years. Depictions of Alexander and his diving bell were created over 1,000 years after his death, adding to the romanticism, but not to the story’s credibility.

Between 1505 and 1510 Leonardo DaVinci wrote a set of papers and notes called the Codex Leicester. In these papers, he wrote on topics such as ‘The Ashen Glow of the Moon”, “The Movement of Water”, and a study of fossils. Included in this was a study of how fish swim, along with rudimentary sketches of a submarine-like vessel which would allow humans to remain underwater. The Codex was never published during DaVinci’s lifetime, but they contain astonishing, advanced ideas for the time. Incidentally, the Codex Leicester was purchased by Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates in 1994 for just under $31 million. Adjusted for inflation, it is the most expensive manuscript ever sold.

In the late 16th century, the Zaporozhian Cossacks of Ukraine developed flat bottomed boats called chaikas to attack their Turkish enemies. These vessels could be rowed while partly submerged, and used a ballast system consisting of bales of reeds. While not a submersible, its success as an attack vessel was noted, and respected.

A truly submersible vessel was designed by Englishman William Bourne in 1578. He was not a particularly educated man, but learned greatly from the experienced mariners he served with. He was a ship’s gunner, and later a mathematician, author, and inventor. He wrote several works of technical nature, including his 1578 publication “Inventions or Devices.” In it, he drew up plans for an underwater boat, made of wood, powered by oars, and covered in a layer of waterproof leather. But Bourne never built this vessel, and it remained purely conceptual.

A vessel of similar design to Bourne’s was sponsored by German mathematician and physician Magnus Pegelius, and launched in 1605. However, the vessel immediately sank and became stuck in the mud.

Dutchman Cornelius Van Drebel launched the first ever successful submersible in 1620. His design was similar to Bourne’s; made of wood, and sheathed in greased, waterproof leather. The vessel successfully passed trials at both 12 feet and 15 feet in the river Thames, and was able to maneuver under its own power. He subsequently developed larger versions of this design, and legend has it that even King James I took a trip in one of the larger versions.

But interest in submersibles waned in the 17th century and Navies found them to be useless as vessels of war. Several other designs had been attempted, with varying success. In 1775, a unique contraption called “The Turtle” was designed and built by David Bushnell, for use against the British Royal Navy during the American Revolution. It was launched in New York Harbor on September 7, 1776, with a crew of one man, Sergeant Ezra Lee. It was an egg-shaped vessel, somewhat like a large wooden barrel, with hand-cranked, single propeller propulsion. Sgt. Lee was to maneuver the Turtle to the warship HMS Eagle, drill a hole in its hull using an auger, and affix a time-delayed bomb, or torpedo as it was referred to at the time. Several attempts were made, but the auger struck metal instead of wood, and Lee had trouble keeping the Turtle submerged under the ship. Although Lee successfully operated the Turtle, the attack was abandoned. The explosive was released and it drifted into the East River, where it exploded. Another attempt was made on October 5th, but The Turtle was spotted, and he was forced to turn back. There would be no future attempts however, as the Turtle, and its transport sloop were destroyed in the Hudson River on October 9th by three British warships. Despite its less than stellar results, it is the first use of a submarine during combat.

Robert Fulton, who later built the first commercially successful steamboat Clermont, designed and built the submarine Nautilus, and it launched in 1800. Its hull was made of copper sheets over iron, and had the now-familiar tubular design. With a two-man, hand-cranked screw propulsion, it also featured an ingenious collapsible sail structure for surface propulsion. Its horizontal fins, or dive planes, looked much like that of modern submarines, and a leather-encased snorkel device was used for fresh air. Fulton, who lived in France at the time, successfully launched the Nautilus, which performed well in several tests for the French Admiralty, even destroying a 40 foot sloop in a combat test. Napoleon Bonaparte was keen on building several of these, but Fulton had the vessel taken apart due to several leaks. Napoleon then labeled Fulton as a cheat, and the French declined any further involvement. Fulton then turned to the British, and then the United States to fund his submarine, with no success.

An obstacle for 19th century submarine designers was propulsion. Steam power could not be used while submerged, and so, submarines were limited to manpower for propulsion. A useful submarine also has to be large enough to carry the crew, but as the size of the vessel increased, so did the manpower required to operate it. By the early 1800s, it had been 200 years since Drebel built the first submarine, but the technology had hardly advanced.

When the American Civil War began in 1861, the newly formed Confederate States of America had no real navy to speak of. The 30 ships it did have were mostly commandeered US Navy ships that were stuck in southern ports at the time. Of those 30, only about half were seaworthy. The Confederate States could not compete with the Union’s industrial might, and relied heavily on imported goods from the north, especially wheat and corn. Most of the southern farms were invested in crops such as tobacco, cotton, and sugarcane instead of food crops. The Union knew this, and used its naval supremacy to blockade critical southern ports such as Norfolk, Charleston, Savannah, and New Orleans, to deprive the south of imported food, and prevented exports of cotton and tobacco to Europe.

The Confederate navy was forced to rely on innovation rather than brute force. They built strong ironclads to defend its ports, formidable commerce raiders that could outrun Union warships but still overpower merchant vessels, and speedy blockade runners to slip past the Union fleet. The CSS Manassas became the first ironclad warship to engage in battle during the Battle of the Head Passes on the Mississippi River, in October of 1861. It was not the first ironclad ever built, as the British and French began building ironclads a decade earlier, and ironclad floating batteries were used during the Crimean War.

The first ever engagement between ironclads famously occurred March 8-9, 1862, at the Battle of Hampton Roads, between the USS Monitor, and the CSS Virginia. Both ships proved impervious to the other’s shelling, and the result was a tactical draw.

Starting in 1863, the Confederate Navy began developing its “David Class” of semi-submersible torpedo-boats. These “Davids”, as they were called, were not fully submersible, but designed to operate just at the surface of the water. This allowed for very little surface area for the enemy to hit. Since it remained at surface level, steam power was used, as ventilation was still possible. Its cigar shaped wooden hull lne with a single screw propeller, although a smoke stack rose about 10 feet out of the water. While it looked much like a submarine, it was still at its core a surface vessel.

Instead of guns, its weapon was a 10 foot long spar-torpedo; a very simple weapon consisting of a long spar, or pole, protruding from its nose with a 60 pound explosive attached to its end. The Davids were to sneak up on an enemy ship at night, ram it at high speed, punch a hole in its hull, and embed its torpedo within before releasing it, and get away unscathed. If all went as planned, it would avoid being itself damaged in the explosion.

The first of these vessels was the CSS David, which attacked the warship USS New Ironsides in Charleston Harbor on the 5th of October, 1863. The explosive detonated, causing a huge plume of water which rained down on the David, flooding her funnel, and extinguishing her boiler. Several of its crew abandoned ship, believing they were sinking, but returned after realizing she was not sinking. Its boiler was restarted, and it safely made its escape. Additional, and larger, David-class vessels were built between 1863-1865 and were more of a threat and a nuisance rather than a destructive force to Union ships.

The Confederates learned of the launch of the Union submarine USS Alligator in 1861, and desperately needed to get a true submarine of their own into action. In 1862, an experimental submarine called the Pioneer was built in New Orleans by engineers James McClintock and Baxter Watson, with funding provided by Horace Lawson Hunley. This private venture set out to create a submersible to combat Union warships on Lake Pontchartrain in Louisiana. The Pioneer was sleek, with its central cylinder sandwiched between two conical ends. Made from riveted iron sheets salvaged from old boilers, it was 30 feet in length, and required one man to manually crank its single screw for propulsion. Unlike the David class torpedo boats, the Pioneer had a mechanism at its top where a torpedo could be attached to the hull of an enemy ship. Operating as a privateer ship, the Pioneer made several successful test voyages, and destroyed a collection of small rafts and a schooner. However, before it could be used in action, Union Admiral David Farragut captured New Orleans in April of 1862, and the Pioneer was scuttled to prevent it from falling into Union hands. However, the vessel was recovered by Union forces, and it was studied, and documented.

With New Orleans under Union control, McClintock, Watson, and Hunley were forced to move their operation to the Park and Lyons Machine Shop in Mobile, Alabama. They improved on the design of the Pioneer, with a second submersible vessel which was not officially named, but has been referred to as the “Pioneer II”, and also “American Diver.” It was longer, at 36 feet, and initial efforts were made to use an electric motor, and then steam to power the vessel, but neither method could provide the power to produce sufficient speed. Ultimately, a hand-cranked screw propellor was installed, and required 4 men to operate it. In February of 1863, it was towed out to Mobile Bay for a test, where it was swamped in rough currents, and sank.

Undeterred, Horace Lawson Hunley raised private funding from E.C. Singer, who was involved in top secret projects for the Confederacy. James McClintock and Baxter Watson were asked to improve on the “Pioneer 2”, and built a third submarine. McClintock wanted it to have more power, and to be able to move freely in all directions. This resulted in a vessel of 39.5 feet in length, with her height a few inches greater than her width of 4 feet. This vessel also was unnamed during its development, but was called the Fish Boat, Fish Torpedo Boat, and the Pioneer III.

Once again, McClintock attempted to use an electric motor for propulsion, and then a steam engine, but neither could produce enough power. Ultimately, he turned back to manpower, and designed a crankshaft which required 7 men to operate, with an 8th man operating the vessel’s rudder. It had two ballast tanks that could be flooded by opening valves, and which could be emptied using hand pumps. It was extremely cramped inside, and all on board had to remain seated, or otherwise hunched over. Its diving planes allowed for vertical mobility, and 2 small hatches, at its fore and aft, opened to raised conning towers.

During its trials, the Pioneer III reached a maximum speed of 4 knots. Travelling a distance of just 5 nautical miles would take over 75 minutes of constant cranking at top speed. The crew operating the vessel needed incredible stamina for any meaningful attack.

Its initial design called for a floating torpedo attached to a 200 foot long tether. This required the vessel to dive under its target, pass between the sea bottom and the enemy ship above, and drag the floating torpedo across the surface until it struck the target. In July of 1863, shortly after receiving news of the devastating losses at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, the “fishboat” performed a demonstration in the Mobile River for Confederate officials. The vessel dove under an old coal barge, and dragged its floating torpedo until it struck the vessel. The barge was blown to bits, and the submarine reappeared safely on the other side. Admiral Franklin Buchanon was extremely pleased with this test, and wrote to General P.G.T. Beauregard in Charleston, writing, “I am fully satisfied this vessel can be used successfully in blowing up one or more of the enemy’s IronClads in your harbor.” Beauregard agreed and ordered the submarine to be put on rail cars and sent to Charleston Harbor immediately.

It arrived in Charleston on August 12, 1863, along with James McClintock, and investor Gus Whitney. A crew of 8 men were formed and immediately began testing the sub in Charleston Harbor. But Beauregard was impatient, wanting the sub put to use immediately, and he handed the project over to Lt. John Payne. On August 29th, the vessel was moored at Ft. Johnson on the southern shores of Charleston Harbor, where it was preparing to make its first attack. For reasons that can only be speculated, the vessel suddenly and unexpectedly sank, killing 5 of the 8 crewmen. Witness testimonies of the sinking are conflicting. Some claimed the wake of a passing ship swamped the vessel, flooding the sub through its open hatches. Others say it was tangled in the mooring lines of another ship and was pulled over on its side, flooded, and sank. Beauregard immediately hired divers Angus Smith and David Broadfoot to find the vessel, and bring her to the surface.

Shortly after the accident, Horace Lawson Hunley arrived in Charleston, and demanded the operation be handed back to him and his team. General Beauregard agreed, and McClintock and Watson got to work with repairs, while Hunley sent for his own crew of men from Mobile, where the vessel was built. It was around this time that E.C. Singer named this 3rd submarine the H.L. Hunley, to honor the tireless dedication Hunley had poured into the creation of an operational submarine. This was a privateer vessel, and was never purchased or commissioned by the Confederate government, and therefore did not receive the CSS designation.

By October 15th, the Hunley was ready for another trial, with Hunley himself serving as its captain. Hunley and crew took the vessel into the harbor, where it dove under the CSS Indian Chief, and disappeared, and did not resurface. After several weeks of searching, the Hunley was finally found, deep in Charleston Harbor, on November 7th, 1863. Its bow was buried in the mud, and its stern was floating upward, as if the sub took a nosedive, straight to the bottom.

Angus Smith and David Broadfoor once again retrieved the Hunley using chains and cables, and when the hatches were opened, all 8 crewmen were found dead inside. Horace Lawson Hunley was reportedly still holding a candle in the forward conning tower. After investigating the vessel, it was found that the forward ballast tank valve had been left open, and it filled with water, causing the sudden nosedive. The vessel’s keel weights had also been loosened by the crew, indicating they knew they were in trouble. The men were found in contorted positions, with the appearance of having been terrified at the time of their deaths.

Within 6 weeks, 13 men had lost their lives, including the sub’s primary benefactor, Horace Lawson Hunley. The tragic accidents involving the experimental submarine became controversial as news spread around Charleston. General Beuaregard considered the Hunley a failure and wanted nothing more to do with the project, saying, “It’s more dangerous to those who use it than to the enemy.” News of the accidents and the deaths of the crewmen spread to spies too, and the Union learned of the submarine’s existence in Charleston Harbor. Union ships were ordered to anchor in shallower waters, and to hang chains and ropes over the sides as a deterrent. Similar tactics were used in the 20th century in the form of anti-submarine nets.

But work on the Hunley continued, backed by Lt. George Dixon and Lt. William Alexander, as the Union blockade was stifling and a countermeasure was desperately needed. Beauregard was hesitant, but eventually agreed to allow the project to continue, under one condition: he insisted the Hunley could only operate on the surface, and would not dive under the surface.

With this mandate, the Hunley would need a different method to deliver its torpedo. Dixon turned to the spar-torpedo, and attached a 16 foot spar to the Hunley’s bow, with a 135 pound explosive at its end. The torpedo would be rammed into the hull of its enemy, and could be exploded either on contact, or by manual detonation.

Lt. Dixon was the new Captain of the Hunley, with Lt. William Alexander as his First Mate. To fill out the remaining crew, Dixon recruited volunteers from the naval ships in Charleston Harbor, which was not difficult. But Alexander was recalled to the CSS Alabama and was forced to leave the Hunley; an order that saved his life. Following the war, Alexander wrote, “We had no difficulty in getting volunteers to man her. I don’t believe a man considered the danger which awaited him. The honor of being the first to engage the enemy in this novel way overshadowed all else.” Dixon and his volunteers trained 4 days a week, from sun-up to sundown, throughout December 1863 and January 1864, learning all the nuances of the vessel, and testing its capabilities and limits. On one occasion, Dixon took the Hunley out close enough to Union ships of the blockade to hear the men on board singing songs.

It was winter, and the Atlantic waters were rough. The Hunley and its crew were ready but were waiting for a break in the weather, and calmer seas to make their first attack. They also needed an outgoing tide, as the manually propelled Hunley would not be able to overcome an incoming tide. Finally on the moonlit night of February 17th, 1864, the weather was clear, the seas were calm, and the tide was outgoing. It was time for action. The Hunley departed Breach Inlet of Sullivan’s Island, and voyaged out to open waters in search of a target. Dixon spotted the 1,260 ton sloop of war USS Housatonic, and ordered the attack. Approaching from the north, the Hunley approached unseen, and positioned itself to approach the Housatonic from behind.

At approximately 8:45 PM, lookouts on the Housatonic began shouting. They saw something in the water several hundred yards away, but couldn’t make out what it was. Some even thought it was a porpoise. The Hunley continued its approach, with its crew managing all the speed they could muster. By the time the crew of the Housatonic realized they were under attack, the Hunley was too close for Housatonic’s 11 guns. Alarms were raised, and the Housatonic’s crew fired their pistols at the Hunley, and the bullets pinged off the sub’s iron hull. The Hunley rammed the hull of the Housatonic with its spar torpedo, striking about at the mizzenmast, at the rear of the ship. An incredible explosion erupted of wood, metal, smoke, water, and men. The blast opened a gaping hole in Housatonic’s hull, and she immediately began sinking. Its lifeboats were launched, but in less than 5 minutes, Housatonic slipped beneath the waves, taking the lives of five of its 160 crew.

The Hunley destroyed its target. Mission accomplished. It was the first time in history that a submarine sank another vessel in combat. But following the attack, the Hunley was nowhere to be found. Housatonic sailor Robert Flemming later claimed that he saw a blue light off in the distance, about 45 minutes after the attack. Lt. Dixon had arranged to send a flash of blue lights to soldiers at Battery Marshall at Sullivan’s Island, if his mission was successful. On February 19th 1864, Lieutenant Col. Olin Miller Dantzler at Battery Marshall stated, “The signals agreed upon to be given in case the boat wished a light to be exposed at this post as a guide for its return, were observed and answered.” But the Hunley and its crew never returned. It had completed its mission by sinking the Housatonic, but was lost with all 8 of its crew. Exactly what happened to it, and why, remain a mystery.

Union ships immediately searched the area, in an attempt to recover the Hunley, and possibly put it to use. It was assumed the sub would be found within the wreckage of the Housatonic, whose masts protruded above the water’s surface. But they found nothing.

Diver Angus Smith claimed to have discovered the Hunley in 1876, as he was still under contract to recover wrecks in Charleston Harbor. Smith sent a letter to General Beauregard, informing him of the discovery. Smith described the location as being “just outside, on the seaward side, of the wreck of the Housatonic.” His efforts to recover the vessel were unsuccessful, and the Hunley faded into legend. But Smith’s description of the location ultimately turned out to be accurate.

In 1970, underwater archaeologist Dr. E. Lee Spence of the Sea Research Society discovered the wreck of the H.L Hunley, shouting, “I’ve found the Hunley!” when he surfaced. He carefully plotted the location of the wreck, without the aid of GPS, and several days later, his associates returned to the coordinates and dove the wreck again. Within days, Spence reported his discovery to the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology and the National Park Service, but he didn’t report his discovery to the media until 1975. In 1978, the Hunley was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, using Spence’s coordinates. Dr. Spence surveyed the wreck again in 1971 and 1979, and recorded his observations.

In 1994, Spence published his book, “Treasures of the Confederate Coast” in which he wrote of the discovery of the Hunley, and included a map with an X marking the spot of its location.

In April of 1995, the wreck of the Hunley was “rediscovered” by diver Ralph Wilbanks, of the National Underwater and Marine Agency, or NUMA for short, funded by adventure-novelist Clive Cussler. The NUMA team uncovered one of the Hunley’s conning towers, under 30 feet of water and 3 feet of mud.

There has long been a heated debate between E. Lee Spence and Clive Cussler over who should get credit for finding the Hunley. Cussler died in 2020, but the debate continues to this day. It is a complicated and messy string of events involving lawsuits, money, politicians, and government agencies, and is not a rabbit hole I wished to go down for the purposes of this episode. However, ownership of the Hunley ultimately ended up with the state of South Carolina.

South Carolina State Senator Glenn McConnell created the Friends of the Hunley, a non-profit organization, and tabbed businessman Warren Lasch as its Chairman, to raise funds for the recovery of the long-missing sub. A massive archaeological and research effort took place, and preparations were made to begin recovery. A metal truss was constructed over the 40 foot long vessel, and divers guided 30 individual slings through tunnels underneath the vessel. Each individual sling was injected with inflatable foam which would mold to the shape of the vessel. Finally on August 8, 2000, people from all over the world came to see the H.L. Hunley as she was lifted out of the water. Thousands gathered in Charleston Harbour and cheered upon seeing the long-lost legendary sub.

The vessel was taken to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, where she was placed in a tank of cold water to preserve her structure. The inside of the vessel was then opened, where all 8 crewmen’s remains were found in place, still where they sat when they died. They were buried on April 17th, 2004 at Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina, next to H.L. Hunley and the 7 others who died in Charleston Harbor during testing. The burial ceremony followed a 4.5 mile procession through Charleston, and was viewed by tens of thousands of people.

The Hunley’s structure was found to be damaged in numerous places. Its rudder was broken off, and found underneath the vessel. There is a large hole in its aft ballast tank, among other damage. But none of the damage can be confirmed as the cause of its sinking, as much of the damage could have come from spending over 100 years on the bottom of the ocean. Interestingly, the Hunley’s ballast pumps were not set to pump water out, suggesting that the Hunley, possibly, did not flood with water, and the men did not drown.

So what caused the submarine to sink? Friends of the Hunley, at hunley.org, explains 4 popular theories: damage from the explosion of the torpedo, a collision with an approaching Union vessel, a lucky shot from a pistol through the conning tower, and the Hunley not being able to return to shore due to an outgoing tide. We may never know, but the team of Hunley researchers continue to investigate.

Of all the artifacts found, one in particular has an intriguing backstory. According to legend, the Hunley’s captain, George Dixon, was given a $20 gold coin by his sweetheart, Miss Queenie Bennett, and Dixon carried it with him at all times. On April 6th, 1862, Dixon was shot during the Battle of Shiloh, with the bullet striking him in the upper leg. But the bullet actually struck the gold coin in his pocket, which absorbed some of the impact. While still badly injured, Dixon’s life was, apparently, saved by the gold coin. For over a century this legend was told and retold, without any evidence to prove the legend to be true.

When the Hunley was finally brought to the surface and the remains of George Dixon could be observed, the legend came to life. In his pocket was a $20 gold coin, dated 1860, and very clearly warped, as if a bullet had struck it. Inscribed on one side of the coin are the words, ‘Shiloh, April 6th 1862, My life Preserver, G. E. D.’ George Erasmus Dixon. Forensic examination of the coin found traces of lead, as would exist if it were struck by a bullet. In addition, Senior Archaeologist of the Hunley, Maria Jacobsen, reported, “We found a healed gunshot wound on Dixon’s left upper thigh, with minute lead fragments embedded in the bone.” So often, legends turn out to be just that, especially from the world of maritime history. But the evidence suggests this legend is true.

Today, the preserved wreck of the H.L. Hunley and its artifacts, including George Dixon’s gold coin, can be seen in person at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, in North Charleson, South Carolina.